The Legacy of the Washitsu in Contemporary Interiors

When we think of a traditional Japanese interior, the first image that comes to mind is of a minimalist room defined by simple lines and natural materials. The image evoked is that of a washitsu, which literally means “Japanese style room”. The washitsu has a distinctive aesthetic identity dominated by its two main elements: the akarishoji sliding doors and the tatami matting on the floor. Thanks to the freedom with which these two traditional features have been reinterpreted, they continue to be used in contemporary interiors.

Tatami flooring in the interior of A House in Kashimanomori by Shigenori Uoya Architect and Associates

The akarishoji—now referred to simply as shoji— were originally movable screens of rice paper on a wooden lattice frame that could be used to create additional rooms when needed. Besides providing necessary privacy, the fine rice paper allowed for a soft white light to enter the room. The singular charm of this illumination, as well as the suggestive shadows created on the rice paper, are the main reasons for the survival of shoji to the present day.

A wide variety of materials used in contemporary reinterpretations of shoji have broadened the possibilities for its uses. Screens made of glass or modern resilient rice paper can now be used even in gardens or bathrooms. Still, the original uses of shoji as room dividers and window shades continue to be the most popular because of the unrivalled benefit of achieving privacy while admitting light.

The second representative element of the washitsu —delicate tatami mat flooring— was one of the features less likely to survive because of its incompatibility with modern lifestyles. Nevertheless, to this day, contemporary homes preserve this distinctive Japanese feature as well as many of the traditions related to it.

In older days, tatami mats were used in most rooms of the house, but today they are reserved for more private areas like bedrooms or sometimes small guest rooms. It is important to highlight that this tradition is not only maintained in stylish designer homes or expensive hotels. Even in newly built apartments for standard Japanese families it is quite common to find a small washitsu with tatami mats.

The association of the tatami mat with the idea of domestic life is so prevalent in Japanese culture that the size of rooms is still expressed in the number of mats that could fit in it, instead of using other common units such as square meters. More interestingly, many lifestyle traditions related to the use of tatami are maintained even in houses with hard flooring.

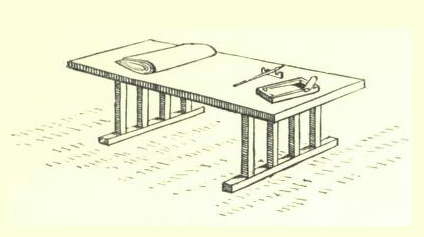

Some distinctive Japanese traditions, such as the removal of the shoes or the custom of sitting at floor level, are closely associated with the delicacy of the mats. Since tatami does not allow for heavy furniture to be placed on it, a wide range of furniture has developed specially for this flooring, such as the cushion called zabuton or the traditional low writing desk. Today, this type of furniture has developed into contemporary computer desks which can be used while sitting at floor level in a comfortable legless chair (of which there are also countless models). This type of low furniture is widely popular among the Japanese, especially with the younger generations.

Traditional writing desk on tatami floor, from Japanese house and their surroundings by Edward Morse (1886)

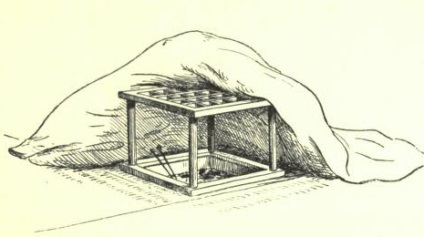

Traditional Kotatsu, from Japanese house and their surroundings by Edward Morse (1886)

A particularly esteemed piece of low furniture that has survived Westernization —and for a good reason— is the kotatsu. Originally, the kotatsu was a wooden structure placed on top of a cooking stove located in the middle of the room. Blankets and futons were placed on top of this structure to retain warmth at night, while during the day the concentrated heat under the blankets could warm up the feet. The contemporary electric kotatsu, which is a table with a heater underneath, can be found in most Japanese houses regardless of their style.

Clever adaptations of shoji and tatami mats along with low furniture are a great example of how the flexibility of Japanese interiors — which is so admired by Westerners— does not only apply to the use of space. A flexible approach to the reinterpretation of traditional elements has made them compatible with contemporary and Western lifestyles.

A Beatiful Washitsu (Japanese traditional room) at Kashiwaya in Kyoto, Japan by Wataru Hasegawa Architect Studio

Photograph: Daijiro Okada

See also: 12 Tatami Room Designs by ZenVita Architects

Looking for inspiration? ZenVita offers FREE advice and consultation with some of Japan's top architects and landscape designers on all your interior design or garden upgrade needs. If you need help with your own home improvement project, contact us directly for personalized assistance and further information on our services: Get in touch.

SEARCH

Recent blog posts

- November 16, 2017Akitoshi Ukai and the Geometry of Pragmatism

- October 08, 2017Ikebana: The Japanese “Way of the Flower”

- September 29, 2017Dai Nagasaka and the Comforts of Home

- September 10, 2017An Interview with Kaz Shigemitsu the Founder of ZenVita

- June 25, 2017Takeshi Hosaka and the Permeability of Landscape

get notified

about new articles

Join thousand of architectural lovers that are passionate about Japanese architecture