Shigeru Ban and the Virtue of Impermanence

Pritzker Prize winning architect Shigeru Ban, is renowned for his innovative use of cheap recyclable materials like paper and cardboard tubes to provide emergency shelters for disaster victims. Most recently he has been in the news for providing relief aid to earthquake victims in Ecuador and in Kumamoto, Japan. In this special article for ZenVita, Edward J. Taylor reviews Ban’s career and examines his designs in the light of Japanese traditions of impermanence.

Shigeru Ban Picture by 準建築人手札網站 (CC BY 2.0)

Shigeru Ban Picture by 準建築人手札網站 (CC BY 2.0)I believe that it was in Alex Kerr’s classic book Lost Japan that I first learned that the average lifespan of a Japanese house is a mere 20 years. Once the initial surprise wore off, it began to make sense. That number roughly correlates to a single generation, and in a culture where the eldest son inherits property, he and his family might decide to build something that takes in the latest styles and comforts. Not to mention the fact that Japanese architecture overall has long been subject to the Buddhist principle of impermanence, being a land of frequent earthquakes and typhoons. Following this logic to its extreme, how about a house that's not meant to last at all?

Renowned Japanese architect Shigeru Ban has built his career on the theme of invisible structure, where he deemphasizes structural elements by melding them into the overall design. This theme could be expanded beyond the choice and presentation of unobtrusive building materials, to the invisibility of those same materials once the structure itself is gone. In being recyclable or reusable, they simply vanish.

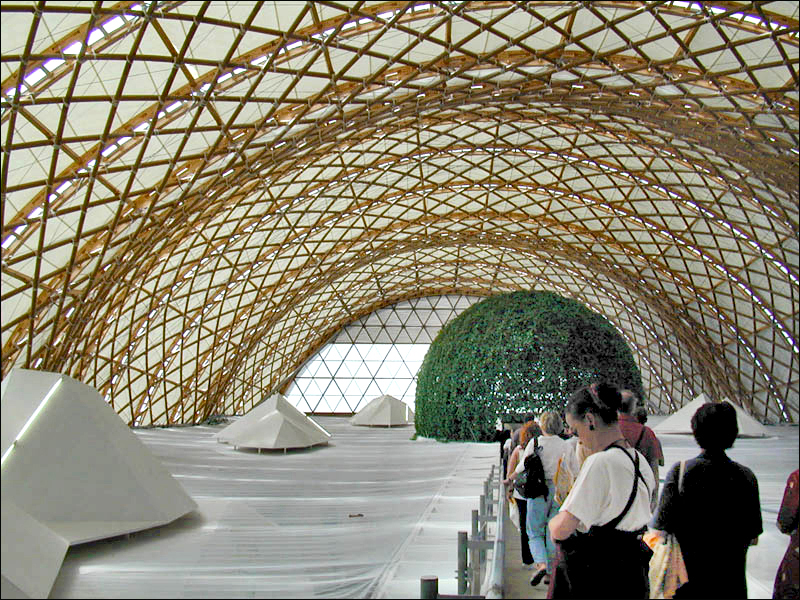

This concept found its genesis in 2000, in the form of the environmentally friendly Japanese pavilion at the World Expo in Hanover, Germany. Ban's focus was not the completed structure, but rather the recyclability of the materials after the building's inevitable destruction at the expo's conclusion.

Six years later, Ban was invited to design the second Pompidou Center in Metz, France. Too poor to afford Paris' notoriously high rents, he built an office atop the Pompidou itself, using paper tubes and wooden joints. Ban and his students lived and worked in the 35-meter long structure for six years without paying a single euro in rent.

Pompidou Center in Metz. Picture by Guido Radig (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Pompidou Center in Metz. Picture by Guido Radig (CC BY-SA 3.0)Not long after this, Ban began to think that he was not doing enough for wider society, his work being mainly for the benefit of the wealthy and privileged. He felt that in the case of earthquakes, it was the architect who was responsible if any of their structures were to collapse. And even if the architect were to accept responsibility, they would usually be unable to build a temporary shelter for the displaced, being too busy designing the next project for yet another wealthy client.

With this in mind, Ban designed his first refugee shelter for those displaced by tribal violence in Rwanda in 1994. He didn't have to look far from home for his following project, designing shelters from paper tubes and beer crates to house survivors of the 1995 earthquake in Kobe. These structures proved so popular that some chose to live in them for as long as 10 years. Ban and his work would continue to appear after nearly every major disaster since, including the most recent tragedies in Kumamoto and Ecuador.

The Takatori Catholic Church that Ban designed for parishioners after the Kobe quake was subsequently moved to Taiwan after that country's 1999 disaster, and has since gone on to become a permanent structure. Ban began then to reassess the definition of permanent. He feels that even a structure built with reusable and recyclable materials can become permanent if it is loved. Some of Ban’s most beloved, truly permanent structures include the Aspen Art Museum, the Onnagawa train station, the Oita Prefectural Art Museum, and of course, the Pompidou Center in Metz.

But more than any single work, Ban is best known for his international reputation. Winner of the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize and named by Time Magazine as one of the 21st century’s top innovators, the borderless nature of Ban’s projects began to appear began while he was training at the Southern California Institute of Architecture. While his earlier studies at Tokyo University of the Arts, had grounded him in themes of traditional Japanese architecture, it was in America that he began to reshape this mold by breaking it down to its fundamental geometric elements. He discovered that the already minimalist squares and rectangles of the Japanese home could be replicated and framed by waterproofed paper tubes. Historically Japan is renowned for constructing buildings devoid of nails, preferring instead fitted joints that allow a structure to ‘dance’ in an earthquake, without getting pulled apart. Ban cleverly mimics this in his practical use of fabric tape.

Oita Prefectural Art Museum. Picture by 大分帰省中 (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Oita Prefectural Art Museum. Picture by 大分帰省中 (CC BY-SA 4.0)Ban seems to relish taking on design challenges, working with and around limitations imposed by scarcity of materials and construction codes, while managing to work with a budget as minimalist as his designs. This flexibility and innovation is leading our problem-laden world society toward eye-catching, permanent design solutions. In these insecure days of dwindling resources, expanding landfills and increasingly frequent natural disasters, Ban’s brand of temporary architecture is more necessary than ever.

Edward J. Taylor is the author of the Notes from the ‘Nog blog, and a contributing editor of Kyoto Journal.

For more innovative designs from Japanese architects visit the ZenVita Projects page. ZenVita offers FREE advice and consultation with some of Japan's top architects and landscape designers on all your interior design or garden upgrade needs. If you need help with your own home improvement project, contact us directly for personalized assistance and further information on our services: Get in touch.

SEARCH

Recent blog posts

- November 16, 2017Akitoshi Ukai and the Geometry of Pragmatism

- October 08, 2017Ikebana: The Japanese “Way of the Flower”

- September 29, 2017Dai Nagasaka and the Comforts of Home

- September 10, 2017An Interview with Kaz Shigemitsu the Founder of ZenVita

- June 25, 2017Takeshi Hosaka and the Permeability of Landscape

get notified

about new articles

Join thousand of architectural lovers that are passionate about Japanese architecture