Kengo Kuma and the Erasure of Architecture

In the opening paragraph to his book Selected Works, Kengo Kuma writes that his ultimate aim is to ‘erase’ architecture; to find a way to make architecture actually disappear. Quite ironic words from the man who has been chosen to construct the National Stadium for the Olympic Games, one of the most visible events in the world. While the plans for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics cannot be said thus far to have been trouble free, the choice of Kuma is a solid one.

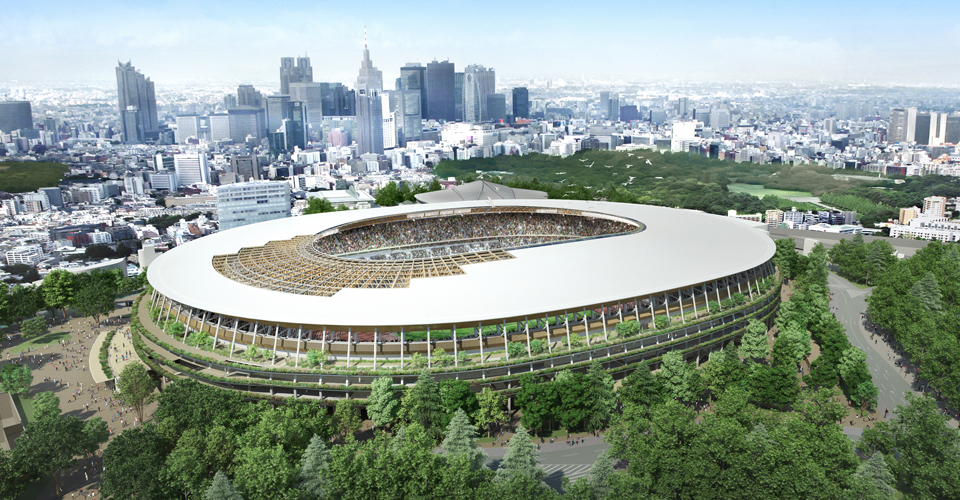

Kengo Kuma’s design for the Olympic Stadium © Japan Sport Council

Kengo Kuma is arguably Japan’s best-known architect, and his works can now be found on nearly every continent. Born in Yokohama, he received a Masters in Architecture at Tokyo University, before spending two years as a visiting scholar at Columbia University. He cut his teeth during the bubble years of the late 1980s, a time when his subtlety of design would not have been appreciated alongside the gaudy displays of overconsumption that defined the architecture of the period.

While some of his earliest works resembled the formula of the day, namely the unrestrained use of concrete and glass, it was only after the burst of the bubble (and perhaps the drying up of funds available to these monuments of excess), that his buildings began to take on the economy of form and materials by which he has become renowned. His use of wooden slats and bamboo draw most directly from the machiya houses of Kyoto. Yet Kuma’s ‘erasure’ goes beyond this, almost to an erasure of Japanese societal identity itself. The blending of these minimalist structures with the physical environment harkens back even as far as the prehistoric days of the Jomon period, in that his designs resemble somehow the most simple Shinto shrines of those early days. Shinto, the indigenous folk religion of Japan, actually exemplifies the idea that there is no separation between the soul of man, and the spirituality of nature.

Osaka’s Louis Vitton Headquarters. Image by by Hiromitsu Morimoto

I suppose such a parallel is easily drawn considering that so many of Kuma’s buildings can be found in remote rural areas. But it can be equally said about those works found in the heart of the city. While admittedly his Nezu Museum is located on a patch of borrowed forest, inside it is easy to forget that you are merely blocks away from one of Tokyo’s busiest and chicest neighborhoods. The glass of Osaka’s Louis Vuitton headquarters has been treated to make it appear as a stone monolith. Tokyo’s Suntory Museum rises like a springtime forest with the sun louvering through. The tangled vine foyer of Kyoto’s Cocon Karasuma almost camouflages the taller structure behind. And Omotesando One looks as if it isn’t even there.

Omotesando One. Image from Wikimedia Commons

I personally came across Kuma’s name for the first time a couple of years ago, in an interview that intrigued me enough to stay in a ryokan inn of his design, Yamagata prefecture’s Ginzan Onsen Fujiya. The town itself has a unified look of two parallel rows of Taisho-period inns flanking a central canal. And while yes, the Fujiya does differ a great deal in design, it looks as if it has simply been brushed in. A far cry from other hot spring towns I’ve visited over the years, and their contemporary concrete monstrosities. (I’m looking at you here Mr. Ando.) The only word I can use to describe the structure is ‘delicate,’ befitting the soft-touch of the service there. The full-length slatted front glass did most certainly give the effect that indoors was out and outdoors was in, almost as if I were amongst the other bathers clopping down the lane to their next bath, to the point that I self-consciously kept checking that my yukata robe was modestly tied shut.

Ginzan Onsen Fujiya © Kengo Kuma & Associates (kkaa.co.jp/)

While I am saddened to say farewell to Tokyo’s previous 1964 Olympic Stadium, which had always been one of my favorite structures in the city, Kengo Kuma’s minimalist designs show a stripped down stage that will shift focus to the rightful place -- onto the athletes themselves. Kuma’s estimated construction costs come in at approximately half of what Zaha Hadid’s now-scrapped design had been, perhaps an ironic wink at the excesses of the days in which he first started out in the field. And therein lies the ultimate irony, in the choice of the man who could be considered the most ‘traditionally Japanese’ of Japanese architects, being entrusted with the structure that will best exemplify the most futuristic of the world’s cities.

Edward J. Taylor is the author of the Notes from the ‘Nog blog, and a contributing editor of Kyoto Journal.

For more innovative designs from Japanese architects visit the ZenVita Projects page. ZenVita offers FREE advice and consultation with some of Japan's top architects and landscape designers on all your interior design or garden upgrade needs. If you need help with your own home improvement project, contact us directly for personalized assistance and further information on our services: Get in touch.

SEARCH

Recent blog posts

- November 16, 2017Akitoshi Ukai and the Geometry of Pragmatism

- October 08, 2017Ikebana: The Japanese “Way of the Flower”

- September 29, 2017Dai Nagasaka and the Comforts of Home

- September 10, 2017An Interview with Kaz Shigemitsu the Founder of ZenVita

- June 25, 2017Takeshi Hosaka and the Permeability of Landscape

get notified

about new articles

Join thousand of architectural lovers that are passionate about Japanese architecture